February 5, 2016 by Rick Spillman

February 5, 2016 by Rick Spillman

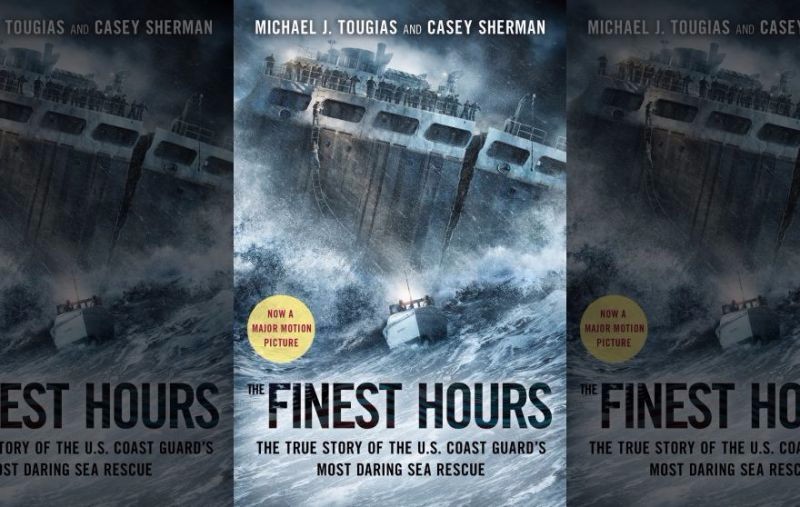

On February 18, 1952, the T2 tanker SS Pendleton broke in half in a Nor’easter, in 60-foot seas and 70-knot winds off Cape Cod. The US Coast Guard Chatham Lifeboat Station dispatched BM1 Bernie Webber with a crew of three in a wooden 36-foot-long motorized lifeboat to search for the Pendleton. In almost impossible conditions, Webber and his crew crossed Chatham bar, located the ship and rescued 32 of the Pendleton survivors in a boat designed for 12, including the crew. It is considered to be the greatest small boat rescue in history. The movie, “The Finest Hours,” starring Chris Pine, Casey Affleck, and Holliday Grainger is a dramatization of the rescue, based on a book of the same name by Michael J. Tougias and Casey Sherman.By Rick Spillman – “The Finest Hours” is far from a perfect movie. Nevertheless, it recounts a remarkable story of heroism at sea that is well worth retelling. For anyone who has spent any time around ships, it is also hard to resist a movie in which one of the lead characters is a grumpy chief engineer.

February 18th was a very bad day for T2 tankers. A few hours after the SS Pendleton broke in half, a second T2 tanker, the SS Fort Mercer, suffered the same fate, in the same storm, in almost the same area. Unlike the Pendleton, the Fort Mercer managed to send out a distress call shortly before the ship broke in two. The Coast Guard mobilized as many boats and cutters as it could manage to rescue the survivors of the Fort Mercer, leaving literally only four guys and a wooden lifeboat available to rescue the men on the Pendleton when it was sighted from shore eight hours later. Chris Pine plays the coxswain Bernie Weber who was put in command of a very small boat facing a very large and angry ocean.

Remarkably, the engine room in the stern of the Pendleton remained relatively intact after the ship broke apart. Chief Engineer Ray Sybert organized the 33 surviving crew. Casey Affleck plays Ray Sybert as a taciturn, unflappable and more than a bit curmudgeonly chief engineer, who succeeds in holding both the crew and what remains of the broken ship together. His performance reminded me of several chief engineers I have known.

The movie tells the story of the rescue, cutting between the Chatham Lifeboat Station, Webber’s lifeboat, and the engine room and deckhouse of the Pendleton. I found the scenes on the Pendleton to be especially effective. The engine room looks and sounds like a steam turbine powered ship. I swear that I could almost smell the hot oil and steam.

The events aboard the ship are largely fictionalized. There were also several technical anachronisms which I suspect were dreamed up to facilitate telling the story. To my eyes, at least, they weren’t enough to be overly distracting. And, given that I have never actually been in the engine room of a T2, it is possible that I have got the details wrong, as well. It is also possible that there are larger issues that I missed. Despite the obvious dramatization of events on the wrecked ship, however, the underlying historical basis for the story is unchanged. Chief Sybert kept the crew working together and the plant on-line, which is an accomplishment worth noting.

Before Bernie Webber and his crew can get to the Pendleton, they first have to cross Chatham bar, which in the winter Nor’easter is a nightmare of breaking waves capable of tossing or rolling the small lifeboat with ease. The scenes in the movie give the viewer an up close and personal view of what it must have been like to make the seemingly impossible passage across the bar. Fortunately, the computer animation mixed with footage shot of the lifeboat in the wave tank doesn’t overwhelm the scene.

Even with these scenes working well, the movie almost sinks in the first 15 minutes when it seems to be primarily a retro-1950s love story. An even larger problem is that the main character, Bernie Webber, is portrayed as a self-effacing, wholly unself-aware, and uncertain Coast Guard coxswain, whose perky and beautiful girlfriend, at least initially, frightens him. In the first scene, Webber needs to be goaded out of the car to meet the young woman. He is worried whether she will like him, inspite of the actor’s movie star good looks. For too much of the movie, Webber has the look of a deer caught in headlights.

There are also far too many exclamations of, “But that is a suicide mission,” or “they will never make it over the bar” which telegraphs to the audience that they will indeed make it through. A subplot about an earlier failed rescue has potential but goes basically nowhere.

Despite the movie’s shortcomings, I found myself wholly engaged as Webber and his crew maneuvered back and forth in storm swells, dragging the crew of the Pendleton from the roiling waves into the tiny lifeboat. Overall, “The Finest Hours” is a movie worth seeing and a rescue well worth remembering.