Larissa, Greece Yannis Behrakis Perspective by Yannis Behrakis

Larissa, Greece Yannis Behrakis Perspective by Yannis Behrakis

As Athens faces growing pressure to reach agreement with lenders to avoid financial chaos, an angry Greek public feels the pain of cuts following a six-year recession, with unemployment more than double the euro zone’s average.

Reuters photographer Yannis Behrakis travelled from Athens to northeastern Greece and back via the Peloponnese region in the south in search of the remnants of a once-flourishing Greek industry, which has suffered a 30 percent drop in production from its peak.

When I was a child the word “ergostasiarchis” (industrialist) was more like an aristocratic title rather than a description for a businessman, Behrakis recalls.

When I was a child the word “ergostasiarchis” (industrialist) was more like an aristocratic title rather than a description for a businessman, Behrakis recalls.

I remember the factory being talked about as akin to the cradle of Greece’s path to the modern world and prosperity. If there are factories, the elders would say, people can work and support the local economy, without needing to leave the motherland in search of work abroad.

All these thoughts were bouncing around my mind as I drove north seeking to document the deindustrialisation of Greece. Hundreds of factories have closed down in the past three decades for a number of reasons, but the recent financial crisis has become the tombstone of Greece’s industrial era.

All these thoughts were bouncing around my mind as I drove north seeking to document the deindustrialisation of Greece. Hundreds of factories have closed down in the past three decades for a number of reasons, but the recent financial crisis has become the tombstone of Greece’s industrial era.

In my 2,500 km trip around Greece I witnessed the sad reality of once-flourishing Greek industry.

Near the town of Larissa, south of Mount Olympus, I visited a factory that once produced textiles, only to witness rusted gates and signs of squatters living in the once-thriving business.

On a dusty piece of glass next to a leather armchair inside a manager’s office, someone had written, “Please help”. As I drove north towards the glorious snow-capped Olympus, with several deserted industrial structures lying at its feet, I couldn’t help thinking about the twelve Gods of ancient Greece that once lived on top of the legendary mountain.

On a dusty piece of glass next to a leather armchair inside a manager’s office, someone had written, “Please help”. As I drove north towards the glorious snow-capped Olympus, with several deserted industrial structures lying at its feet, I couldn’t help thinking about the twelve Gods of ancient Greece that once lived on top of the legendary mountain.

In Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest city, a huge timber factory was devastated by looters and the weather, while another factory in the city’s industrial zone looked like a scene from the post-apocalypse movie “I Am Legend” starring Will Smith.

In Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest city, a huge timber factory was devastated by looters and the weather, while another factory in the city’s industrial zone looked like a scene from the post-apocalypse movie “I Am Legend” starring Will Smith.

While wondering around closed factories in Thessaloniki’s industrial zone, I stepped into a huge structure that looked in relatively good shape but it was clearly deserted. I walked in and came across an artificial Christmas tree still decorated lying on the floor of an enormous storage room. A few steps behind was a closed safe next to a wall calendar of 2011. The scene sent a shiver down my spine: it was as if the world in that spot had ended.

While wondering around closed factories in Thessaloniki’s industrial zone, I stepped into a huge structure that looked in relatively good shape but it was clearly deserted. I walked in and came across an artificial Christmas tree still decorated lying on the floor of an enormous storage room. A few steps behind was a closed safe next to a wall calendar of 2011. The scene sent a shiver down my spine: it was as if the world in that spot had ended.

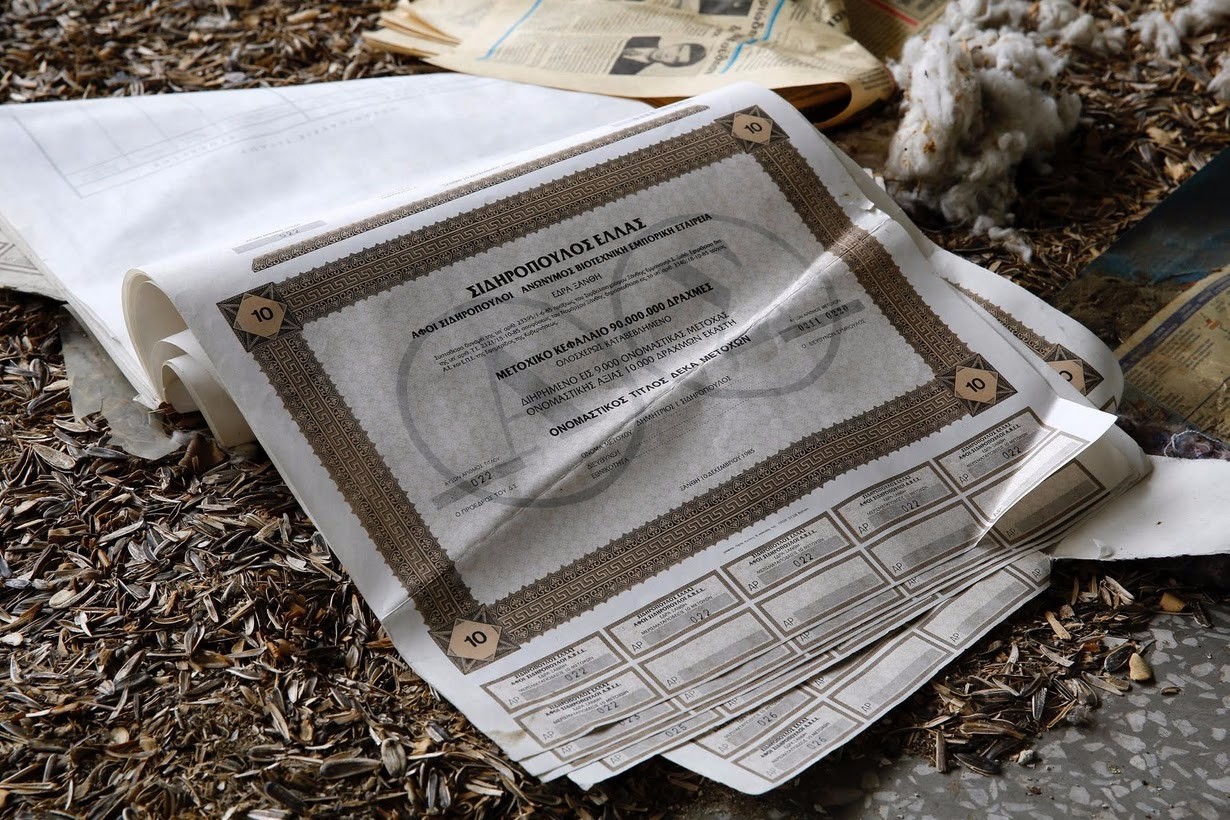

In northeastern Greece, I visited several factories, most of them looted and deserted. In one of them bond certificates from the 1990s lay on the floor next to dried-out nutshells.

In northeastern Greece, I visited several factories, most of them looted and deserted. In one of them bond certificates from the 1990s lay on the floor next to dried-out nutshells.

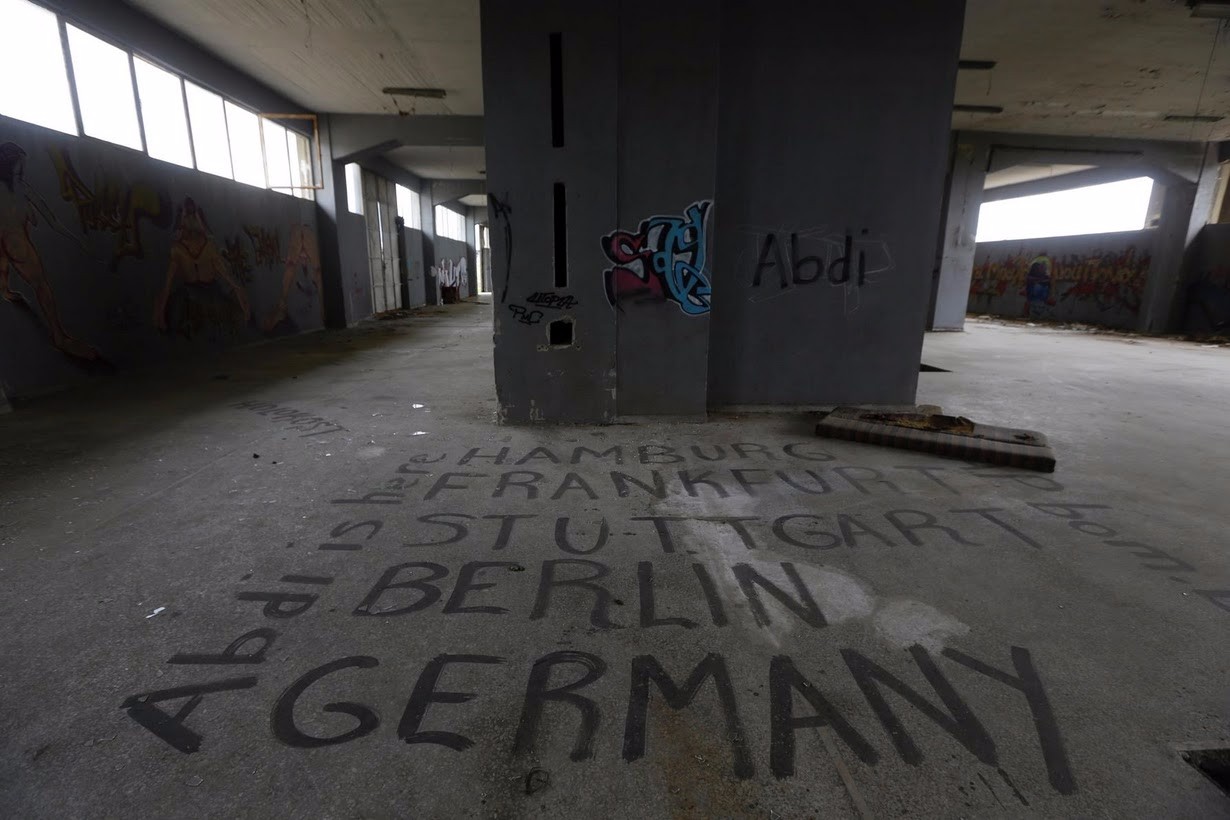

In another building outside the town of Xanthi, the border with Bulgaria to the north, an immigrant who had once lived there, giving his name as Abdi, had written names of German cities on the floor next to some beautiful graffiti by local artists.

In another building outside the town of Xanthi, the border with Bulgaria to the north, an immigrant who had once lived there, giving his name as Abdi, had written names of German cities on the floor next to some beautiful graffiti by local artists.

On my way back to Athens, before driving south to the Peloponnese region, I stopped at the industrial zone in Thebes, a small town north of Athens, in one of Greece’s industrial hinterlands. I wandered through dirt roads on the Sterea Ellas plain in central Greece looking for one of the country’s famous production sites, the Izola home appliances mega-factory, long since closed.

On my way back to Athens, before driving south to the Peloponnese region, I stopped at the industrial zone in Thebes, a small town north of Athens, in one of Greece’s industrial hinterlands. I wandered through dirt roads on the Sterea Ellas plain in central Greece looking for one of the country’s famous production sites, the Izola home appliances mega-factory, long since closed.

Later that day I stopped the car to photograph the Izola factory, a symbol of the sad remnants of Greece’s dying industrial age, and as the sun was about to set, the warm orange-yellow light gave an unexpected beauty to the structure in the distance.

Later that day I stopped the car to photograph the Izola factory, a symbol of the sad remnants of Greece’s dying industrial age, and as the sun was about to set, the warm orange-yellow light gave an unexpected beauty to the structure in the distance.

My last stop was Elefsina, near Athens, where I visited a huge cooking oil factory that closed in the 1990s. A scruffy Greek flag was draped over the rusting gate next to a destroyed fence.

My last stop was Elefsina, near Athens, where I visited a huge cooking oil factory that closed in the 1990s. A scruffy Greek flag was draped over the rusting gate next to a destroyed fence.

Dimitrios, a senior citizen who lived in a humble house just opposite the factory, said he picked up the flag from the factory floor and placed it over the gate because he felt ashamed to leave it lying there. A clocking-in device with over 300 slots for workers’ cards had stopped at 9am one morning in 1996.

reuters

Yannis Behrakis More from

Yannis Behrakis