iloveithaki.gr | apr 2nd 2017

iloveithaki.gr | apr 2nd 2017

dd manias

William Mure was a british colonial officer and classist, in his capacity of resident on the island of ithaki, he had to deal with the following episode, about which he wrote at length (Mure 1852: 46-59).

in 1817, a certain monsieur Soleure arrived on the island of ithaki from Patras and settled in the main town.

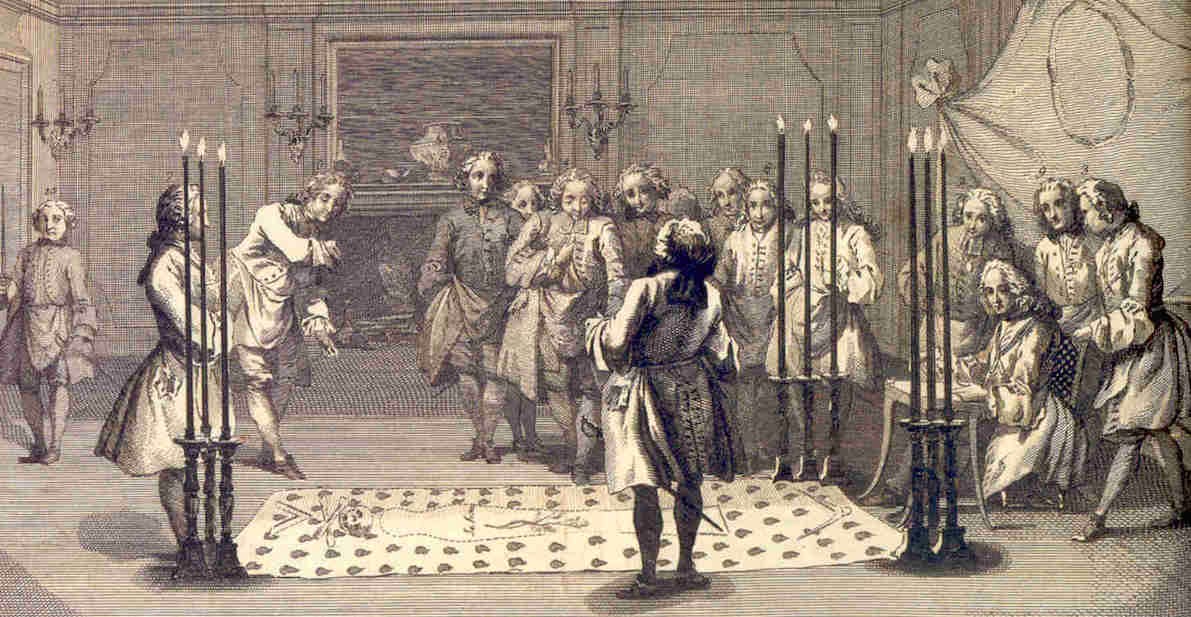

he had served as an officer in the french army but for reasons unknown had fled to greece. though not a nobleman, Soleure was a learnd man of breeding who had married the daughter of a wealthy landowner from patras. his star in local society rose, and eventually he became schoolmaster for the island. in 1823 he helped establish a chapter of the free masons. the lord high commissioner, thomas met land, was promoting the masonry and encouraging all “right-thinking men” to join (CO 136/45: january 5, 1822 PRO): he saw it as an alternative to the filiki etairia, an organisation which was playing a critical role in the greek war of independence (fringes 1973). as we saw earlier, the vast majority of ionian islanders were rapid supporters of the greekrevolution, and so, not surprisingly, the masons membership drive proved largely unsuccessful; only british soldiers and pro-british ionians joined – and only a very small number of them. by casting his lot with the british and by taking a public stance against the war of independence, Soleure made numerous enemies on ithaki.

The masons’ unpopularity continued after the greek war had ended because the group was now so firmly associated with british rule and because it was seen as an impediment to ionian unification with the kingdom of greece. in addition during the 1830s, religion entered the picture in ways more visible than i had in the 1820s. masonry was depicted as the tool of the anti-christ. local clerics preached that it was through masonry that the british sought to destroy the orthodox church. anti-masons feelings ran high. in 1837, for example, under the leadership of the village priests and some local men of “respect”, there was public demonstration and near riot against them. rocks and lemons served as projectiles for the angry mob, but no one was seriously injured. anti-mason leader of the ithakan lodge, soleure bore the brunt of this malevolence.

the usual silence of greek winter’s night in december 1839 was shattered by a young girl’s screams. a peasant girl dressed as a maid burst into the police station and blurted out that there was trouble at her master’s house. when the police arrived at the soleure residence, they foung soleure sitting in the master bedroom in a state of shock. the walls were smeared with blood, but not soleure’s: he had not been the target of the attack. instead, on the floor lay the mutilated bodies of his wife and son. except for a cut on his arm soleure appeared unharmed. at the foot of the bed was a bloody scabbard, but the sword that went with it was nowhere to be found.

when he recovered his wits soleure professed his innocence. a group of masked men, he claimed, had entered his house, beat him and then forced him to watch as they slaughtered his family. but all the evidence was against him. no one had seen the mysterious attackers and no physical evidence could be found in the house to indicate that they had been there. except for the killing of the boy – few greeks accept that a father could kill his own son – this looked like a not very uncommon case of domestic violence. the islanders were convinced of his guilt as a foreigner, he was capable of anything and, as a leader in the union of anti-christ’s – the masons – he was linked to the devilas the priests claimed. the masses were clamouring for “rough justice”. the local greek public prosecutor stalled. a special british prosecutor was sent from kerkira to handle the case, and a british colleague of his from the colonial office agreed to defend soleure. both sides believed him innocent but without additional evidence they could not prove it, and as was usually the case, no one would step forward to give evidence.

at the request of the civil aughorities on ithaki, the metropolitan of kefalonia issued a decree of excommunication and sent his personal assistant to deliver it.

a special mass was held, conducted jointly by the archbishop of the island and the bishop of the deme, a grand procession proceeded through the streets of the town: the archbishop, the bishop, their entourages, the constables, and finally the members of the free masons. here was the unity of churches and state on display.

compliance was demanded: eternal damnation was threatened.

three people stepped forward. the maid testified that soleure often fought with his wife and that, on the night in question, the only voices she had heard coming from the bedroom were those of soleure, his wife, and their son. a barber announced that about a week after the incident he saw walk down to the pier and throw an object into the water. since it was dusk, however he could not determine what the object was, but he was sure as to the identity of the man: soleure. led by the advocate fiscale and some policemen, a crowd gathered at the waterfront. the barber pointed out into the water and a local boy dove in. after a few minutes underwater, the lad emerged. holding aloft the bloodstained sword. with high drama, a policeman produced the scabbard confiscated from soleure’s house. the hushed crowd watched as he slid the weapon into the sheath. the fit was perfect. suddenly, a shopkeeper shouted out from the crowd that he recognized the sword; it was the very one which soleure had tried to sell him six months before the murder. it looked bleak for soleure.

who influenced the decision-making process. the policy of using excommunication as a means of establishing social control was manipulated and transformed by members of the ionian aristocracy into a tool of patronage.

peasants, patrons, priests, and ideology

the policy of co-opting the religious elite and employing excommunication for crime was failure. throughout the 1840s and 1850s, lower-class clerics continued to lead popular protest. perhaps the best example of this is papas Yioryios nodaros, the infamous papas lists, of “bandit priest”. he was the leader of a group of riots which in 1849 wreaked havoc in the region of skala on kefalonia until their defeat at hands of the british army (paximadopoylos-stavrinou 1980; tsoyganatos 1976; hannell 1987). on seventeen occasions during the final twenty- four years of protectorate, lenten carnival celebrations erupted in violence. moreover excommunication clicked in a village, they stated that they had no effect, and without exception, in the 15% of the cases where they had an impact church property was involved.